Press Release

Spiral Dance in a Planetary Nursery

April 18, 2004

Low Resolution (129 KB) High Resolution (273 KB) |

|

Object Name: AB Aurigae |

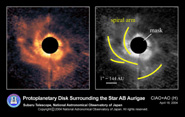

New high resolution near-infrared direct imaging of the protoplanetary disk surrounding the star AB Aurigae shows that this planetary nursery is not the comparatively featureless and smooth place that astronomers had once assumed, but a place where gas and dust swirl in a complex spiral pattern. The new observations are part of a project to study the immediate neighborhood of young stars with greater detail than ever before by combining the large 8.2 meter effective aperture of the Subaru telescope with adaptive optics and a coronagraphic imager.

Young stars only one million years old are known to be surrounded by cosmic gas and dust in the form of a disk (Figure 1). Such disks are the birth place of planets like Jupiter and Earth, and are called protoplanetary disks. Protoplanetary disks are only as large as a solar system, a small place on astronomical scales, and observing such small structures from distances of several hundred light years away is a challenge (Note 1). Radio and infrared wavelength observations have shown that many young stars must have protoplanetary disks, but most of these observations only provide indirect evidence. Direct observation of a disk in optical and infrared wavelengths is very difficult because the brightness of the central young star overwhelms the faint light from the disk. Up until now, only a few unusually large disks and disks that conveniently block the light from the central star have been directly imaged.

A team of astronomers from the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, the University of Tokyo, Kobe University, Ibaraki University and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency have been observing young stars in the constellation Taurus and Auriga using the Subaru telescope and an instrument called the Coronagraphic Imager with Adaptive Optics (CIAO). A coronagraph hides the light from a bright central star to make it easier to detect faint objects near the star. CIAO is designed to be used with Subaru's adaptive optics (AO) system, which removes fluctuations in the light of a star or other astronomical object due to turbulence in Earth's atmosphere. Subaru is the only 8-meter class telescope in the world that has both an adaptive optics system and a sophisticated cooled coronagraph. Cooling minimizes thermal emission from the coronagraph.

When the team observed the star AB Aurigae as part of their project, they were successful in obtaining a direct image of the infrared light of the star reflecting off its protoplanetary disk (Figure 2). Strangely, the disk was not a smooth flat ring, but had a spiral pattern reminiscent of galaxies like the Milky Way. The spiral pattern is complex and cannot be traced by a single line. Analyzing the detailed light distribution of the spiral pattern and taking into consideration the information about the motion of gas in the disks known from previous radio observations, it appears that the spiral arms are trailing behind the direction of motion, as is the case in spiral galaxies (Figure 3). By looking at the disk with the super sharp resolution of 0.1 arcseconds and in infrared wavelengths that are not heavily influenced by material outside the star and the disks, the detailed structure of a protoplanetary disks is finally becoming directly observable.

How can such a spiral structure arise? There are two current theories. One is that the gravitational tug and pull with a companion star causes a spiral pattern. The other is that unevenness in the density of the disk can grow into spiral pattern as the disk rotates, if the disks is massive enough for such a process to occur. In the case of AB Aurigae, there appears to be no companion star, so it is likely that material outside the disk is falling onto the disk and adding mass to the disk (Note 2).

Can planets form from these spiral arms? The answer is unclear. In this case, no planet has been found, nor is there any indirect evidence for a planet. If a planet is present, it is expected to sweep up material in the disk forming a gap in the protoplanetary disk in the shape of a ring. Identifying structures associated with the presence and absence of planets will be an important focal point for future research.

Here is a summary of the scientific impact of the current research:

1.) Protoplanetary disks surrounding single stars are not smooth and featureless as previously assumed. The site of planet formation has a much more complex structure than previously assumed.

2.) How often various structure occur and how they evolve will become a new topic of interest in the study of protoplanetary disks. The discovery of spiral structure will trigger debate on the possibility of forming planets in a disk with such a structure.

3.) Achieving high resolutions of 0.1 arcseconds made the new science results possible. This research gives a foretaste of the exciting science that will become possible with even higher resolution (0.1 - 0.01 arcsecond) studies that the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan is preparing to do at millimeter and sub-millimeter wavelengths through projects such as the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA; Note 3).

The observers will continue their program to obtain direct images of protoplanetary disks using Subaru and CIAO. Detecting new born planets and even heavier brown dwarfs is the teams next big goal.

These results were published in the Astrophysical Journal, Letters on April 10, 2004. (Ap. J. 605, L53)

Note 1: Our solar system has a diameter of about 100 Astronomical Units (AU). One AU is the distance between the Sun and Earth and is about 150 million km.

Note 2: Other examples of protoplanetary disks with spiral patterns include the disk around the star HD141596A observed with the Hubble Space Telescope Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS). In this case the spiral is caused by the gravitational interaction with a companion star 750 AU from HD141596A. Hubble Space Telescope observations with the Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS) have also shown that low density structures called "envelopes" surrounding two stars show spiral like patterns. However, it is difficult to study the structure of dense regions, where planets are likely to form, using optical light. Near-infrared light, which was observed in the current study, is less sensitive to dust in the envelope, and allows the direct detection of the protoplanetary disk itself.

Note 3: The ALMA project is an international collaboration. The ALMA group in Japan maintains a web site.

Figure 1: Schematic Diagrams of the Evolution of a Protoplanetary Disk around a Sun-like Star